|

|

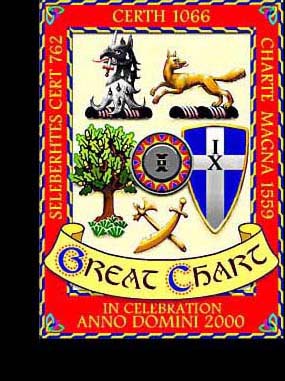

THE GREAT CHART MILLENNIUM SIGN

AND THE EARLY HISTORY OF THE VILLAGE

This village sign, located in Great Chart near Ashford in Kent, UK, was the Millennium project of the Great Chart Society.

It was funded by donations from people of the village and grants from Great Chart with Singleton Parish Council and the 'Awards

for All' and 'Millennium Awards' programmes of Ashford Borough Council.

The sign, made of cast metal and set on an oak post, was installed near St Mary's Church in October 2000. It celebrates

the existence of Great Chart for over twelve hundred years and the article below sets out the author's discovery of the early

history of the village and gives details of related images, names and dates to be found in his design.

AD 762 is an important date in the history of Seleberhtes Cert, or Great Chart as it is now known. By this time the Angles,

Saxons and more precisely the Jutes in Kent had long established their dominance in England. The declining Roman Empire had

recalled its legions in 407 but it had been in occupation for three and a half centuries and many of its citizens had settled,

intermarrying with Celts - the Britons they found on arrival. Then the invading Germanic tribes intermingled with the Romano-Britons

they conquered and the new and lasting Anglo-Saxon era was born. Add a sprinkling of Viking blood, whether first generation

Danish or later Normans, and these are the ancestors of the modern English.

Initially the invaders were pagans led in Kent by the likes of Hengist and Horsa. Their language was rarely written and

for the first two hundred years there was little historic record. This was the most mysterious period of the 'Dark Ages' -

the time of the legendary King Arthur and his often mythical deeds. In fact it was a time when kings abounded everywhere and

Kent was an independent kingdom. In 597 Augustine was sent from Rome to Kent where he converted the Cantware (Kentish) people

and their king, Ethelberht I, to Christianity. After the Romans abandoned England Kent was the first to see (Roman) Christian

revival, and an age of organised learning and civilisation began.

Throughout this time the southern half of Kent was covered with a vast virtually uninhabitable forest - the 'Andredsweald'.

Almost all the population lived near the shorelines, in river valleys and on open downland north of the old Roman road that

ran west-north-west from Lympne to Chart Sutton and on to Rochester. This road cut through the Chart (or Red) Hills and woods

that lay along the north-east fringe of the Weald. It was here in a clearing between the road and the River Stour, and at

the very edge of the inhospitable forest, that the settlement of Great Chart began. Though lack of records make it impossible

to determine exactly when, it may well have existed as far back as Roman times.

The village sign includes a symbolic oak tree, many of which originally surrounded the village clearing. It also refers

to the great 'Domesday Oak' at nearby Godinton Park which, it is said, survived from Norman times until it collapsed as war

was declared on September 3rd 1939.

What is certain is that the village was established and operating a comparatively new invention, a mechanical water mill,

by the year 762. By now assignments, deals and other activities by local kings were being written-up as charters. An original

charter first mentions Great Chart - in passing - when recording that King Ethelberht II (of Kent) exchanged half the use

of the successfully operating mill for some pasture in the Weald. This was the first water mill to be recorded in Britain

and the produce went to his royal 'vill' at Wye. The exchange was made with the monastery of St Peter and St Paul (later

to become St Augustine's) which possibly owned Great Chart at the time. In return the miller and his heirs were given the

right to 'pannage their swine in the Weald forever'. These circumstances confirm Great Chart was long established before 762.

People bravely took their pigs on feeding trips deep into the forest and, apart from the threat of wild animals,

they had to contend with marauding bandits so set up protective encampments at forest feeding grounds called 'dens'. Later

these swineherds' stop-offs became permanent settlements as the forest was cleared (eg. Tenterden, Bethersden, Smarden, Biddenden,

Frittenden and so on). In the charter of 762 Great Chart's first mention was simply listed - in Old English - as 'Cert'.

Thirty-seven years later in a second charter it was further identified as 'Seleberhtes Cert'. Seleberhtes was either the collective

name of the Jutish people settled here or more likely the name of their leader. Cert means rough common or clearing.

The village sign has on its border various names given to the village since its beginning. The first is 'Seleberhtes Cert

762', and in the centre of the sign is an heraldic symbol of a millstone with decoration from period brooches found in East

Kent.

In 776 Great Chart's manor, the village, its lands and much of its produce were hurriedly sold, lock, stock and barrel by

King Egbert (Ethelberht's successor) to Archbishop Jaenberht of Canterbury to raise finances for a Kentish army - especially

professional mercenaries - to rebel against mighty King Offa. Offa was the greedy ruler of all the midlands (Mercia) and most

of the south and who had long since declared himself 'King of all the English'. In that year there was a great battle between

Mercians and Kentish men at Otford as, apparently, a red cross appeared in the sky.

For nine years after this

battle Egbert held Kent, but ultimately Offa took control and retrieved Great Chart and its lands from Canterbury dividing

them up among his followers. After Offa died in 796 his successor Cenwulf decided to reinstate properties, including Great

Chart, back to the ownership of Canterbury. However, the estate went to Christ Church not St Peter and St Paul's - according

to a charter in 799. Essentially the prior ruled and held court at the manor and much of the produce of the village went to

sustain his monks. This ownership continued for hundreds of years through the Norman Conquest and up to the advent of Henry

VIII when between 1536 and 1539 he dissolved all monasteries. He confiscated Great Chart and its lands from the priory but

soon reinstated them to his new Protestant Dean and Chapter in whose administration they remained until Victorian times (though

in a map of the area from 1621 the lands are still attributed to 'Christ Churche').

The village sign displays the silver cross on a blue shield of the arms of the Dean and Chapter of Canterbury Cathedral.

In 892, when all southern England - a much expanded Wessex - was united under Alfred the Great, this village was on the brink

of disaster. A hundred years earlier pagan Vikings had begun their raids on these shores - they first attacked Lindisfarne

on the coast of Northumbria killing the monks and devastating the Abbey. They then made successive raids further south until

in the year 878 the formidable Alfred defeated them, later drawing up a treaty allowing them to settle in East Anglia and

the North East. However, countrymen from their Danish homeland were still on the move and by the late 880s Haesten, a highly

experienced warrior-leader, had mustered huge forces in northern France.

Up to 350 Viking ships sailed from Boulogne

to the south coast of Kent in 892. A massive army of between five and ten thousand men with their women, children and horses

came up the now long-lost Limen estuary (the east-west route of the Royal Military Canal in reclaimed Romney Marsh) and attacked

a Saxon fort near lonely St Rumwold's church, Bonnington, killing all inside. They then moved on and over the next year built

their own giant fortress at Appledore. On hearing of this, resident Danes in East Anglia and elsewhere broke their promises

to Alfred and rose up to join in. At first they made lightning raids out of Appledore under cover of the forest, later the

whole army moved further inland engaged in numerous battles with the English, but after four years they gave up. Some retreated

to East Anglia and others went back to northern France. There they were the forebears of the Normans who returned in triumph

less than two centuries later.

However, it is one of their earliest raids out of Appledore in 893 which concerns

us here. They were looking for 'booty' at any price. Great Chart was a large prosperous settlement by now (even noted as a

'town' by one historian), and it backed onto the dense Wealden forest. There could have been little warning as out of the

trees came the fearsome mob of mounted Vikings - experienced fighting men who had survived all their lives on plundering their

way through northern Europe. They had besieged Paris and attacked Brittany and were pagans who, though having a surprisingly

sophisticated culture as seen in their artifacts, had no concern for those they robbed.

Undoubtedly the surprised

villagers put on a brave fight but, after robbing and killing many of them, the invaders destroyed all they found. Great Chart

was razed to the ground. An ancient legend passed down by villagers says that after the devastation 'Ashford began to rise

and grow out of the ruins.' This is feasible as any English survivor may have escaped along the Stour setting up camp until

it was safe to return. This camp could have been the beginnings of Ashford which has no confirmed mention before this time.

To commemorate this historic occasion the village sign shows an heraldic curved-handled Danish battle-axe crossing a Saxon

'seax' (a single-edged short sword).

In the year 900 King Alfred died and problems with the Danes continued. Another battle between them and Kentish people occurred

two years later. Eventually the area the Danes occupied in eastern England was retrieved and for a while an Anglo-Danish kingdom

was established until new invasions, starting fifty years later, saw its collapse. One such incursion, which may have involved

Great Chart yet again, was in 991 when Olaf Tryggvasson a Norwegian Viking with 93 ships and over three thousand men landed

and savagely attacked Folkestone ravaging a wide swathe of south-east Kent.

By 1016 the Vikings ruled and the

Dane Canute was made King of England (being something of an emporer since he also became King of Denmark, Norway, Sweden and

the Hebrides!), but twenty-six years later Edward the Confessor restored the Saxon line. However he, being half-Norman and

living his earlier life in France, inevitably introduced the influence and interests of the northern French. Before he died

in 1066 without a son he had named Harold, son of the great Earl Godwin, as his heir. Almost immediately Harold had two simultaneous

threats on his hands, one from the Norwegian King Hardrada whose Viking army he defeated at Stamford Bridge, followed by the

fateful landing at Pevensey of William, Duke of Normandy. Harold might have repelled either enemy alone but he sank beneath

the double attack and the Normans - also originally of Viking stock - rose as winners.

William the Conqueror's

great Domesday Survey, completed twenty years after the famous battle at Hastings, was a thorough but very unpopular inquest

unrivalled in the history of Britain. It was a detailed investigation for the purpose of taxation. Absolutely everything of

value was registered. 'So narrowly did he cause the survey to be made', moans a Saxon chronicler, 'that there was not one

single hide nor rood of land, nor - it is shameful to tell but he thought it no shame to do - was there an ox, cow, or swine

that was not set down in the writ'. The entry for Certh (Great Chart) makes clear that it was still in the possession of the

Archbishop of Canterbury and had two mills, a salt-pit, feeding ground for a hundred hogs, and a population of fifty-two -

which was clearly very small compared to its size in Alfred's day before the Viking destruction - and was now worth the yearly

grand total of twenty-seven pounds!

Great Chart was simply entered as Certh in the Domesday Book - obviously a later rendition of Cert. The village sign has 'Certh

1066' included on its border as the second name from the past. (The Conquest date of 1066 is used instead of the survey completion

date, 1086, because of its historic significance).

Domesday concludes this look at Great Chart's Anglo-Saxon beginnings. However, it must be noted that there are two other important

inclusions on the sign. One is the third name (of many) given to the village in the past. 'Charte Magna' was found on a map

made of the Chart and Longbridge Hundred in 1559 - the year of Elizabeth I's coronation. A 'hundred' was a geographical sub-division

of the county for administration purposes, and Longbridge was a boundary-marker in Willesborough.

The other inclusion

is two heraldic crests used by the Tokes who lived at Godinton House for four hundred years and were highly influential in

the village and parish. One is the head of a griffin holding a sword in its beak and the other a fearsome medieval image of

a running fox. These are based on early glass paintings at Godinton. Metal casts of later versions (probably late 18th century)

appear in the brickwork of many local houses.

(Heraldic note: The College of Arms appears to have no record of a griffin crest in Godinton's lineage. Therefore the crest

here - though used at Godinton - is accurately based on one granted in 1546 to a cousin William Tooke, Auditor General to

Henry VIII: 'A gryphon's head erased per chevron Sable and Argent gutte counterchanged holding in the beak a sword in pale

Argent pommel and hilt downwards Gules'. The fox crest may have been granted to John Toke at an augmentation of arms c.1495,

but again without record. However, his descendant, Nicholas, received official confirmation of a golden running fox in 1668:

'A fox courant regardant Gold').

Selected

bibliography and other sources:

Cartularium Saxonicum, W de Gray Birch, 1893.

History and Topographical Survey

of Kent, E Hasted, 1797-1801

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, trans. D Whitelock, 1961

The Jutish Forest, K P Witney, 1976.

The Kingdom of Kent, K P Witney, 1982.

Kentish Place Names, J K Wallenberg, 1931.

Anglo-Saxon England to 1042,

H Finberg, 1972.

Life and Times of Alfred the Great, D Woodruff, 1974.

Roman Ways in the Weald, I D Margary, 1948.

Godinton Park (guide book), C Hussey et al., English Life Publications.

Canterbury Cathedral Archives.

Heralds

visitation records 1530-1668, various publishers.

College of Arms, London.

© Prof David Hall 2000

|

|

|